A Day Among the Dead

A Tour of the Bird Collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Drexel University

Author: Vin Pannerselvam

We were early to the party. I texted Dr. Nate Rice to let him know we had arrived at the 19th Street entrance of the Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS). His reply was exuberant. He was already waiting in the lobby, greeting us cheerfully. I had been half-expecting to meet a grumpy lab scientist who deals with "dead stuff" all day; at the time, I assumed he’d just downed a few too many cups of Joe.

Little did I know, Nate’s text was a pure reflection of his actual character. Dr. Rice is an Ornithology Collection Manager at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Drexel University. He conducts research on the evolutionary biology of Neotropical birds and travels regularly to South America and around the world for fieldwork. His Midwestern charm truly comes alive when he talks about his esteemed collection.

There were six of us from Bucks County, and we had no idea what was waiting for us within the shelves of the Academy’s 250,000 bird specimens. This exclusive tour was a "perk" from Dr. Rice for our volunteer work with the Bird Safe Doylestown program. Though we only started the program a year ago, Dr. Rice was deeply appreciative of the specimens we had collected from the Bucks County Courthouse and the Justice Center.

From Dinosaurs to Ectoparasites

Our first stop was the iNaturalist exhibit, where a live stream of local observations and details about the project covered a display wall. We walked through the main hall where a giant dinosaur stood tall, sharing the space with a kindergarten field trip. It was delightfully chaotic.

We moved through the public corridors of natural history dioramas, through a few more doors and alleyways, and up an escalator. There, we met Dr. Kamila Kuabara, is a Lab Manager at ANS, a Brazilian scientist specializing in the taxonomy and systematics of chewing lice found on birds. For the next 20 minutes, Dr. Kuabara showed us her beloved collection. ANS holds the largest collection of lice specimens in the world, taken from hosts ranging from mammals and birds to humans and flies. She educated us on how these ectoparasites help us understand the morphology, evolution, and genomics of their hosts. Surprisingly, instead of being "icked out," we were fascinated. Next time you find a louse on yourself, don’t panic! Carefully bag it and bring it to ANS—maybe you’ll be rewarded with a private tour, too.

The Lice Collection!

Dr. Kaubara is passionate about the lice collection and how they help us to advance our understanding of ectoparasites.

A Library of Biodiversity

After the lice lecture, Dr. Nate began the "encore" presentation: the bird collection. We started with the most mundane birds, such as White-throated Sparrows. These are, by far, the most frequent specimens submitted by bird collision monitoring programs. The Academy has shelves full of them dating back decades.

I wondered aloud: How many White-throats do you really need? Don’t you stop when you run out of shelf space? The answer was a firm "no." Dr. Nate explained that it is like recording history in real time. Each specimen tells a story not just of the species, but of the ecology of that specific era. It is like adding books to a library; if a library stops collecting, it misses an entire period of literature. Every bird matters. They are the ecological imagery of their time.

Rare Finds and the Prep Lab

Next, he opened the owl shelves. The Snowy Owls immediately captured our attention. Each year, the Academy adds a few to the collection from the Atlantic coast. He also showed us Barred Owls from the West Coast—specimens from the controversial culls intended to save the Northern Spotted Owl.

Barred Owls…

Saving one species while controlling other has a price to pay.

With a mixed feeling of sadness and an unsettling understanding of the "why," we moved to the lab where volunteers prepare bird skins. A Snowy Owl, a couple of starlings, and several other species were pinned to styrofoam boards near the window to dry. Dr. Nate was particularly excited about a Puerto Rican (PR) Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus brunnescens) specimen he recently received from his Puerto Rican colleagues who found a dead bird (salvaged) and sent to the academy’s collection with necessary permits. Unlike our migratory northern Broad-wings, the Puerto Rican subspecies is a year-round resident. So it will be an interesting specimen to study this particular specimen.

“Birds have faster maturity,” he elaborated, explaining it as an evolutionary strategy to maximize reproductive outcomes. They reach adulthood faster and reproduce multiple times in their lifetime, which accelerates the evolution of species diversity. PR Broad-wing specimens are super rare, so we naturally shared his excitement in working on one.

He explained the "bloody" process of preparing skins while we watched Dr. David Peet, a retired surgeon and a few college students work on starlings. The surgeon was teaching the students how to roll cotton balls to fill the eye sockets. If this kind of thing fancies you as a retirement hobby (or anytime), contact Dr. Nate—he will definitely fulfill your appetite (perhaps the wrong choice of words, but you get the point!).

A student volunteer is working on an European Starling.

Every dead bird tells a story of its time. Ecological history is getting recorded here… one bird at a time!

Walking Among Giants, Ghosts and Paradise

We then moved to the extinct and exotic section. When Dr. Rice opened the drawer of extinct birds, our jaws hit the floor. Birds that once darkened the skies—Passenger Pigeons and Carolina Parakeets—sat lifeless on pedestals. It made us weep internally. It made me question the notion that "Humans are rational animals"; it feels like only the latter half of that description is accurate. We also saw Eskimo Curlews, Great Auks, Heath Hens, and the famous Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

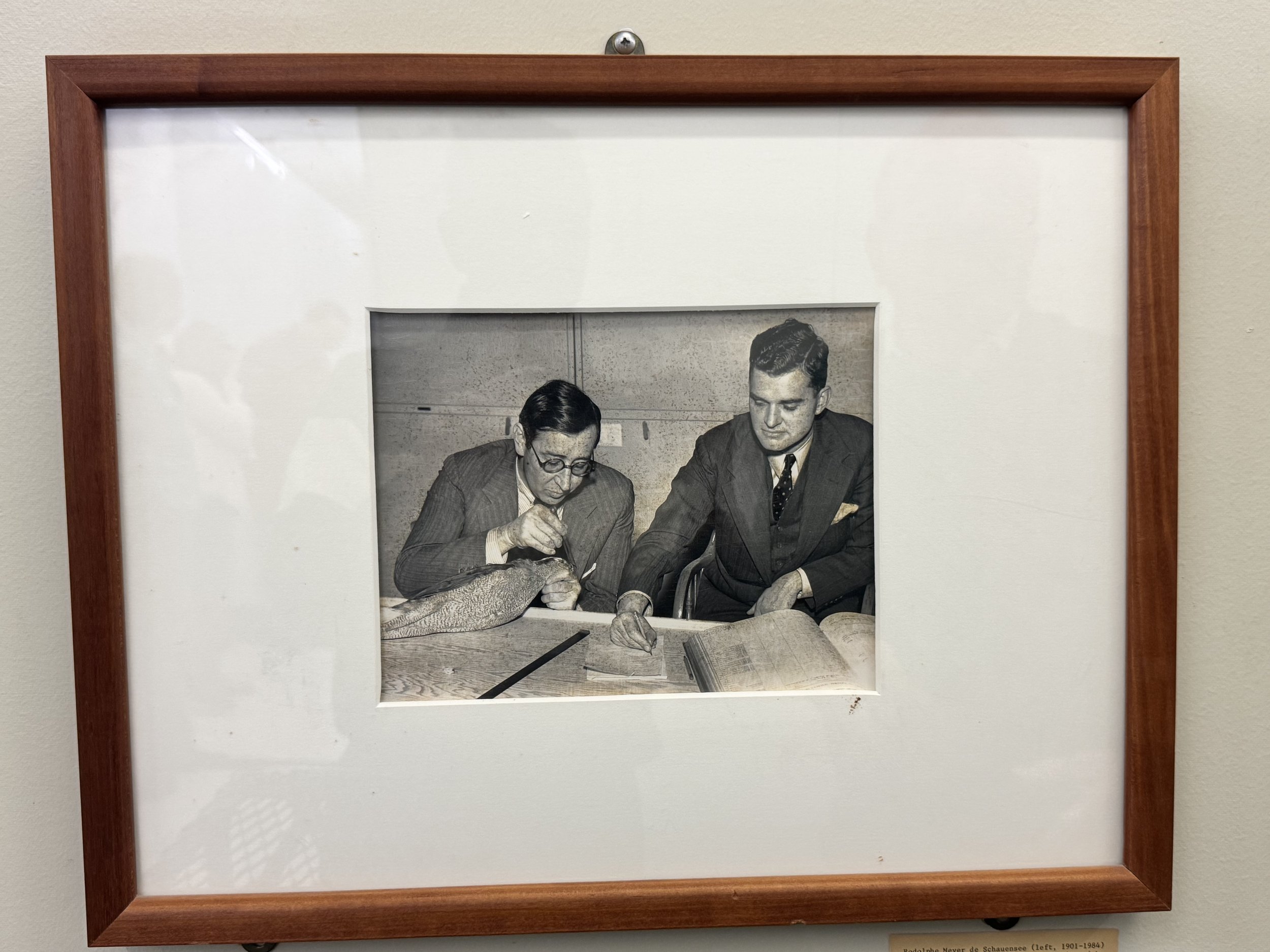

Then came the "hero" section: collections from Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. A few of us shed tears of joy while taking pictures of Darwin’s finches and Wallace’s personal specimens. We even saw an eggshell signed by John James Audubon.

When he opened a few racks further down with a big smile, we knew it was something of special interest. It was the Birds of Paradise section. We were all animated to see the "ballerina bird," the needle-tails, the cotingas, and some of the most colorful specimens in the collection. We talked about ‘The Feather Thief’(it is a fast-paced read if you haven’t) and the feather trade of the past century, where millions of birds were killed for their plumage. Never underestimate the dangers of ignorance fueled by the passions of fashion.

Oology and the Grand Finale

One of the highlights was the oology (egg) section. Dr. Rice opened racks containing eggs ranging from tiny specks to some larger than a soccer ball. Just as we were reaching "enthusiasm exhaustion," he dropped a fact about Common Murre eggs: they can be off-white, beige, dark gray, or teal blue with distinctive brown blotches, all depending on the nest location. Scientists still aren't entirely sure how they do it.

By 1:10 PM, our bellies were complaining, but Dr. Nate wasn't done. He had the same energy he started with three hours prior. He insisted on one last thing: the Penguin collection. We forgot our hunger the moment he pulled out an Emperor Penguin skin that was almost as tall as me (5’3”). The most incredible part wasn't the size, but the collector: a bold printed card proclaimed it was collected by Sir Ernest Shackleton during his 1908 Antarctic expedition!

There is a saying in my native language: You only need food when your ears are not fed. Well, we were fed well that day by Dr. Rice. After thanking him profusely, we finished our packed lunches in the cozy museum cafeteria and headed home, our minds full of natural history.